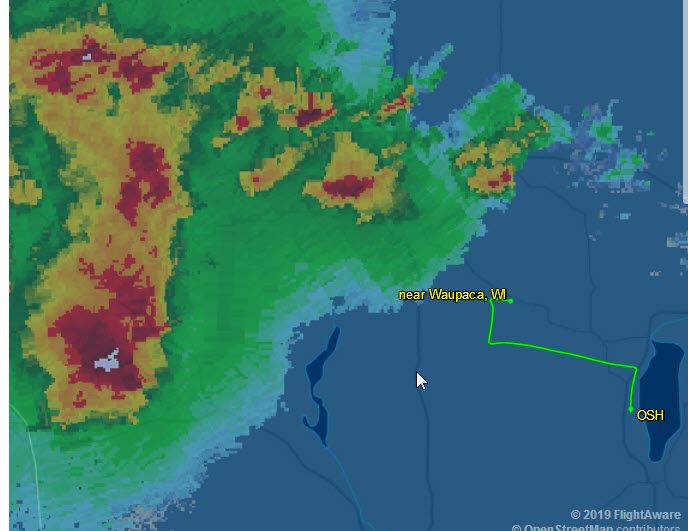

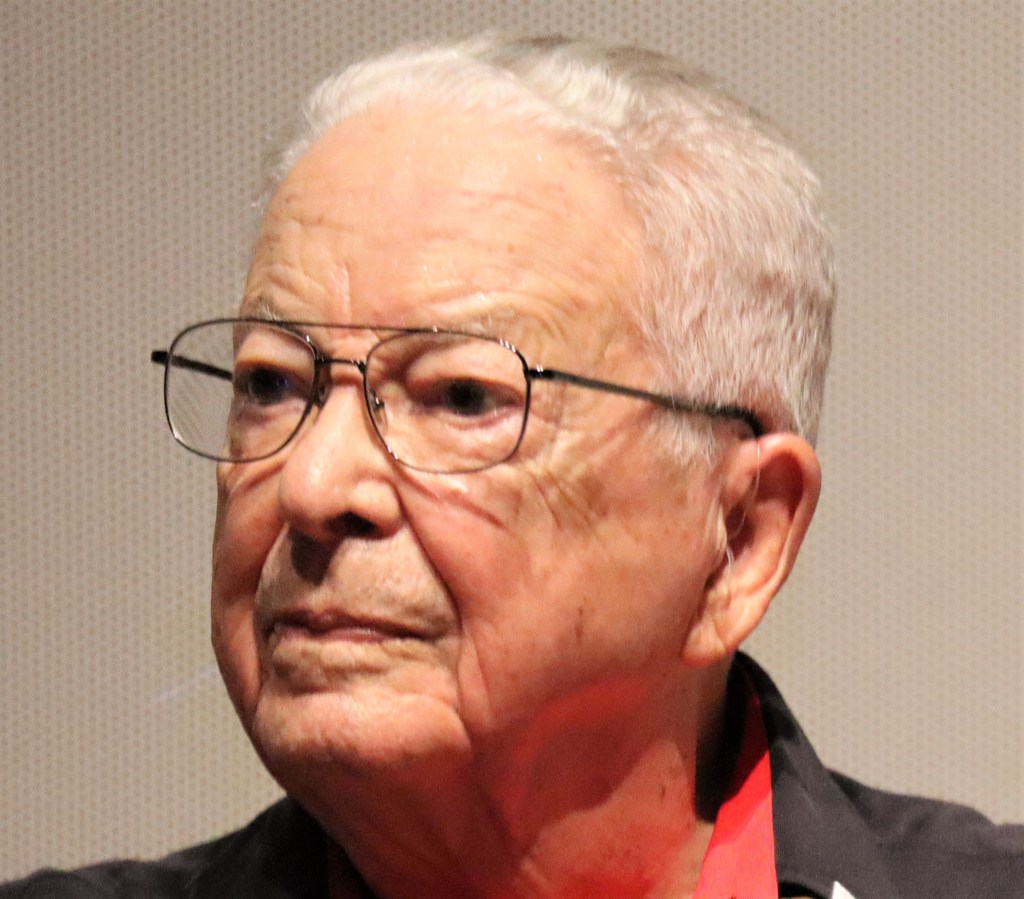

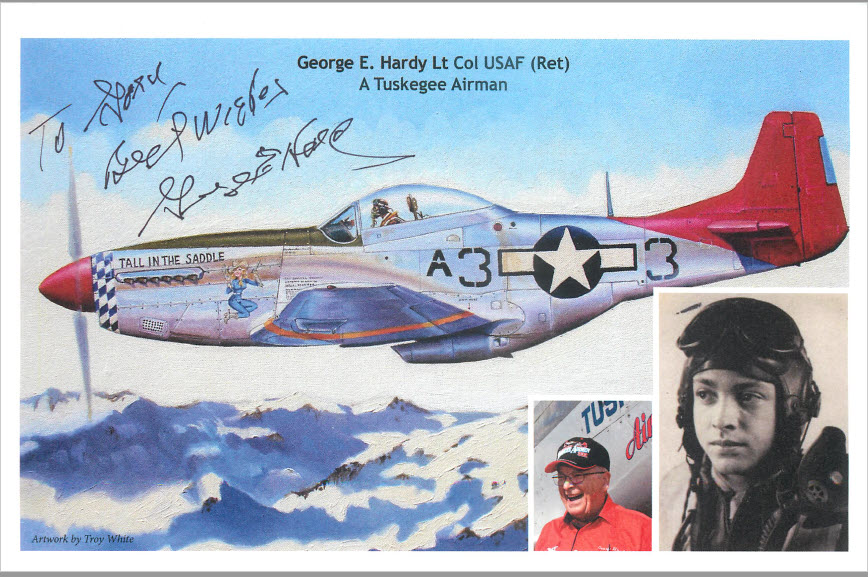

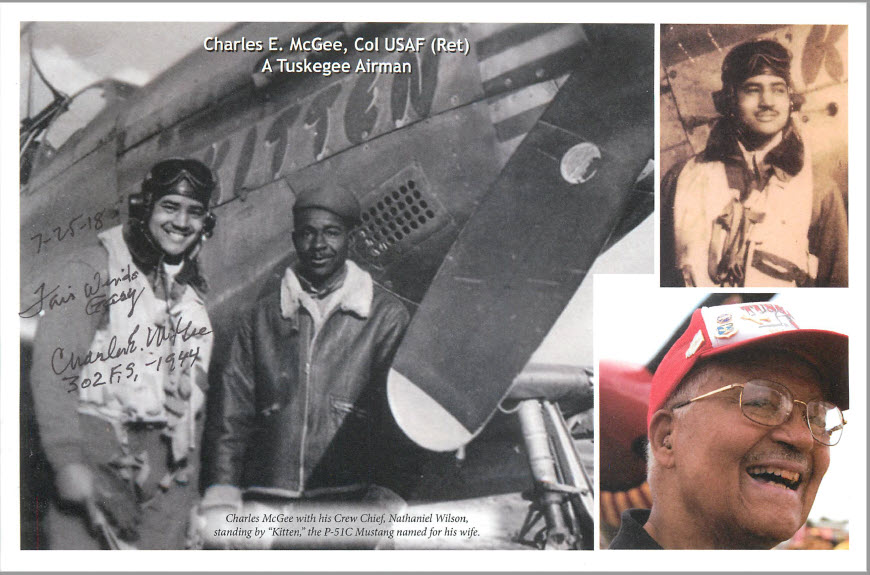

Brigadier Gen. Charles McGee died on January 16, 2022 and was laid to rest in Arlington Cemetery on June 17, 2022. The news left me with sadness as I reflected upon the loss of yet another great American hero. I then began to reflect upon other heroes that I have met, particularly at Oshkosh, including General McGee’s good friend, Col. George Hardy, and famous WASP pilot Nell Bright. Having heard these individuals, and many others, speak in person, I have come to understand that heroes are ordinary people who do extraordinary things. Real heroes don’t wear capes.

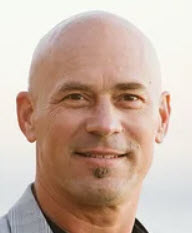

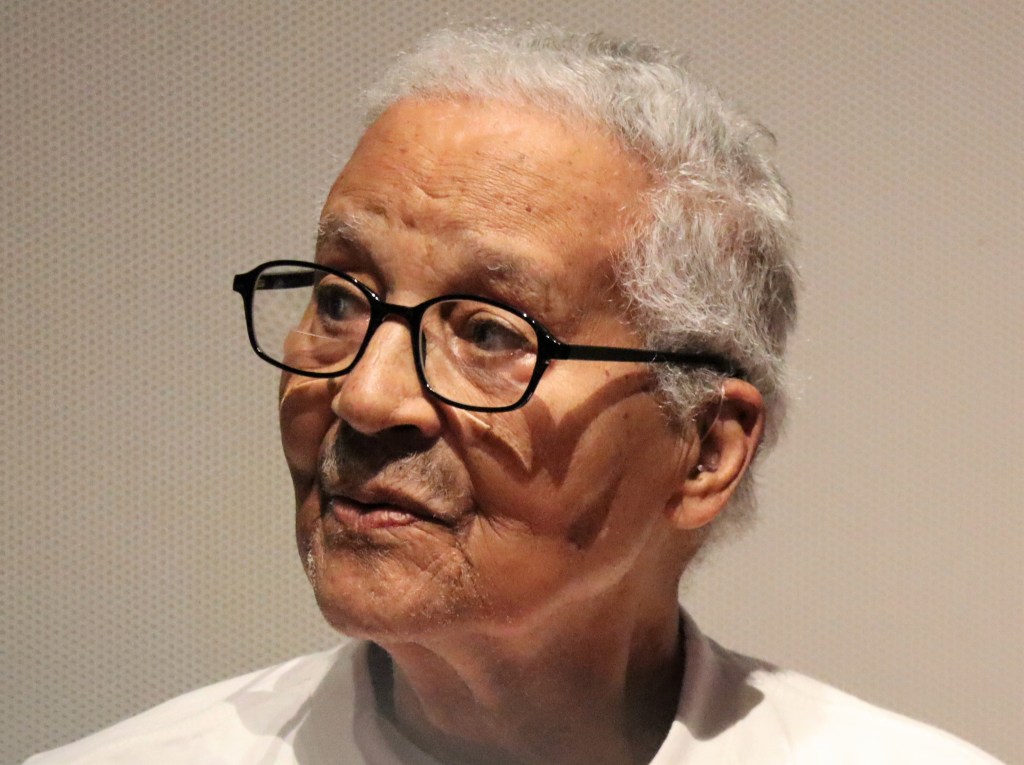

When visiting Oshkosh AirVenture (#OSH, #Airventure), I take advantage of every opportunity I can to see and listen to these heroes of the past and present. I had the privilege of first seeing and meeting General McGee and Col. Hardy at Oshkosh when I visited the Red Tail Squadron promotional video, Rise Above, that was playing in a trailer near the Pioneer airport in 2018. Both men had been part of the Tuskegee Airmen, the famous all-black fighter pilot squadron that trained in Tuskegee, Alabama and was established during World War II .

Resented, not respected, and treated with suspicion at first, the squadron went on to become a highly decorated group of fighters and the squadron of choice for bombers needing escort. Take the time to look up the history of the Tuskegee Airman, their difficult path to becoming aviators, and then their struggle to be allowed to effectively serve in combat. The history is too long to set forth in this article.

What gentle and wonderful men! They were gracious, friendly, outgoing people whose fame did not turn them into prima donnas. On that first meeting, then-Colonel Charles McGee and Col. Hardy autographed a biography of Gen. McGee that was written by his daughter. The book is now a very cherished possession.

At Oshkosh AirVenture 2021, I had the opportunity to hear Gen. McGee and Col. Hardy on two occasions. At the second presentation, they were joined through Zoom video conference by Nell Bright, one the women who served as a WASP. What an extraordinary hour!

Trailblazing is hard work. You have to cut your own path through the brush or carve the trail out of the mountain to get where you want to go. Each yard of path gained is hard-earned. Each of these three individuals was a trailblazer in his or her time. Black Americans were treated as truly second-class citizens, enduring racist attitudes, both legal and de facto, which restricted opportunities that were taken for granted by others. Flying in the 1940s was a man’s game, but the women who became the WASPs demonstrated that they were fully capable and qualified to operate any type of aircraft that was in the fleet. But for all of them, the path was not easy, and perseverance and determination were keystones in their ability to accomplish the great things they achieved in their lives. Self-pity was not to be tolerated in any way.

Both Gen. McGee and Col. Hardy were highly articulate in their presentations, are clearly well-educated men, and they spoke of the efforts that it took on their part to become successful career Air Force officers. They spoke without rancor, without hostility towards others, and expressed a deep-rooted love and patriotism for their country. These men were willing to die for a country for which they were not yet receiving the full benefits of their citizenship. In these times of entitlement, it was heartwarming to see two men who appreciated the greatness of the country they lived in, warts and all.

Nell Bright (nee Stevenson) was a woman pilot when they were not very common, and she was determined to serve her country. She grew up in Canyon, Texas, graduated West Texas State in 1940, and started flying lessons in 1941. She obtained her license in 1942 with 75 hours in a Taylorcraft. Seeing an article in Flying Magazine about women pilots being wanted, she wrote in, was interviewed in Fort Worth, Texas, was accepted, and training began. She received her training at Sweetwater, Texas Avenger Field in 1943. Her personality leaps through the screen, and she was and is clearly a force to reckoned with!

The Women’s Airforce Service Pilots a/k/a Women’s Auxiliary Service Pilots (WASP) was an Army Air Forces program created to train women as pilots to test and ferry aircraft and train other pilots so that men might be freed up for combat. The women had to hold a pilot’s license when they joined but were then trained in Army procedures; predominately, at Avenger Field in Sweetwater, Texas. In an afront to these women, after the war the WASP were disbanded. The final WASP pilot class graduated on December 7, 1944, but the WASP were disbanded two weeks later. General Henry H. “Hap” Arnold supported granting the women Army Air Force Commissions, but the bill to approve it died on a narrow vote in Congress. Arnold ordered that WASPs receive certificates comparable to a honorable discharge. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Women_Airforce_Service_Pilots)

While at one base where they were serving, Nell noted “The commanding officer didn’t particularly want us eating in the officers’ mess, but we were entitled to do so, so we did.”

This “Don’t mess with us” attitude continued when some Tuskegee Airmen arrived on base and were racially segregated. “These trained pilots and officers of the U.S. Army Air Force could not eat in the officers’ mess,” said Nell. “We spoke up and they were finally allowed in, but they had to sit away from everyone else.” Not appreciating the treatment their fellow aviators were receiving, the WASPs went and joined the Tuskegee Airmen at their tables, which was probably quite the scandal.

George and Nell shared that the WASPs received none of the benefits that servicemen did following the war. The Army Air Force deemed them to be federal civil service employees in place for a limited time during World War II. Thirty-eight members lost their lives in training and active-duty accidents. There were no military death benefits. The deceased pilots’ families had to bear the expense of the transport of their loved one’s remains to home. The families of the women lost were not allowed to display the “Gold Star” in their window which represents the loss of a loved one in wartime.

Since they were civil servants, the WASP pilots did not receive G.I. Bill benefits. The failure to recognize the WASP pilots as members of the military was finally rectified by Congress in 1977. The bill gave them “veteran” status and recognized they had served on active duty. They became entitled to Veterans’ Administration Benefits. They were truly the first women pilots to serve in the military.

Nell married and post-war put her economics studies to work by becoming a successful stockbroker in Phoenix, AZ. She was one of the first women to be a stockbroker in Phoenix and she worked until age 85, when she finally retired.

I am so glad that I made a video recording of that presentation in July of 2021. General McGee along with Col. Hardy and Ms. Bright were entertaining and inspiring. I hope to someday edit it so that you all may see it and understand what great people these three individuals were and are. People of this nature are walking history books. I would urge you to take the opportunity to go listen to any of them wherever they may be making presentations around our country. The people who experienced the events, things we only can read about, bring history alive. They bring the human element to historic events, and they bring it to a level to which you and I can relate.

General McGee’s famous four “P’s” are a great set guideposts for all of us; no matter what the circumstances may be in our lives. General McGee called upon people to Perceive, Prepare, Perform, and Persevere. Good words of advice for achieving any goal that we seek in life. Finally, I think General McGee would have these final words for us as we face the roadblocks of life: “Don’t let the circumstances be an excuse for not achieving.”

God bless.

Clear skies and tailwinds

Gary Risley

RizAir Blog 22, © July, 2022

#OSH, #Airventure, #tuskegeeairman, #WASPs #charlesmcgee #georgehardy #nellbright #redtailsquadron #Oshkosh #WWII #aviation #fighterpilot