Thank Goodness for Turbocharged Engines! I would have been in a world of hurt without one on the return trip from Centennial Airport with my Angel Flight passengers. But, more on that in a moment.

When I last left you, dear reader, I had successfully shot the approach into Centennial Airport, taxied to the self-serve fuel pump and filled up, and then taxied over to TAC Air, a local FBO, to pick up my passengers. TAC Air gave great service as always and treated my Angel Flight passengers very well.

As I sat down with my passengers, whom I had previously flown, I explained to them about the balancing act I was doing with regard to our launch time. The clouds overhead were moving higher and starting to break-up, so I decided to wait 30 minutes to launch our flight. We were still going have to file IFR for the departure, but the higher cloud bases gave us more options in the event of engine trouble. The angels understood and agreed.

So why not wait longer and let the cloud cover dissipate even more? Here is the other half of the balancing act. It was late May and the afternoon warms up quickly, and cumulonimbus clouds start building as the day goes longer; particularly, along the La Veta Pass area where I flight path would take us. The goal was to depart KAPA after the cloud bases had lifted somewhat but beat the CB (cumulonimbus) buildup at the Pass. I almost got it right, and that is where the turbocharged engine saved the day.

We were cleared to depart KAPA and received radar vectors to intercept our course to the intersection where we would then turn south. About half-way there, Denver Departure cleared us direct to the Pueblo, CO VOR – good deal! The direct course would save us quite a bit of time. We set up for cruise at 12,000 feet MSL and enjoyed the view as we popped in and out of clouds, followed by clear skies from Colorado Springs on to Pueblo.

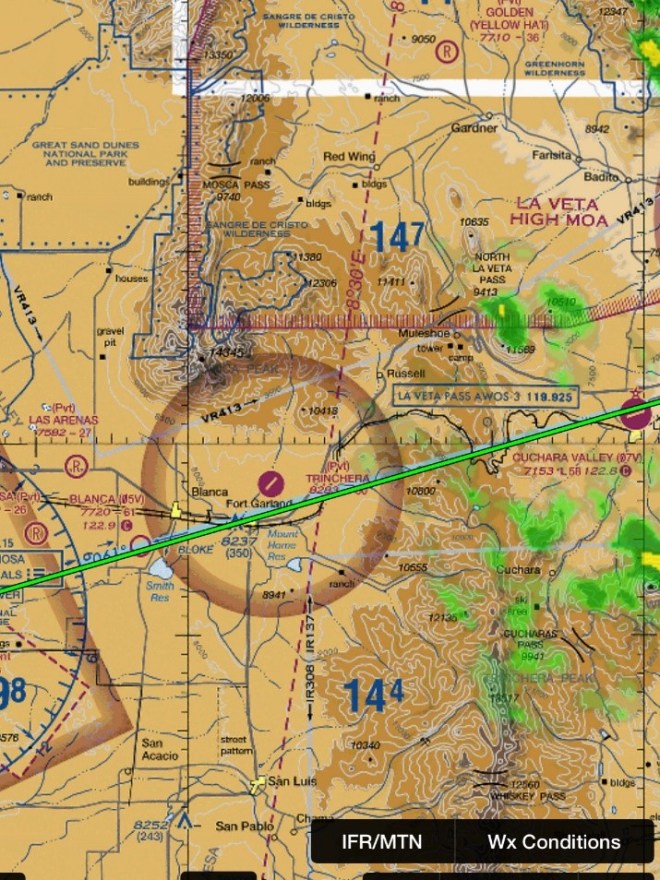

Looking at the ADS-B in-flight weather, I could see CB building up to the south of La Veta pass and it was moving north – the race was on!

There is very high terrain on either side of La Veta Pass. (That is why they call it a “pass” through the mountains!) Almost 12,000-foot mountains to the north of the pass with 14,000 foot Mt. Blanca and it very tall neighbor, Mount Lindsey, a little further north west. Mountains between 9 and 10 thousand feet are to the south of the pass.

As I was approaching Pueblo, I could see the thunderstorms starting to build on the east side of the mountains and a little bit south of the pass. Over a period of time, I could see that the clouds would be blocking the path just about the time I would be arriving.

I advised Denver Center of my concerns. As always, the Lord looks out for fools and idiots (I qualify on both counts), and the controller informed us the military operations area, the La Veta MOA, on the east side of the mountains, just north of the pass had just gone “cold” – no military operations. Normally IFR flights are not allowed to cross active MOA’s.

The controller offered to turn me to the east and allow me to cross north of La Veta Pass. Below is a screen shot of our course as originally planned, you can see some of the build-up, but it was much worse than detected on radar returns shown on the screen shot:

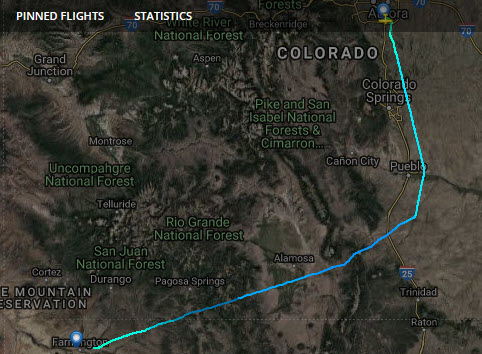

The FlightRadar 24 screenshots that follow show our revised tract:

The problem should become apparent: We are traveling at 12,000 feet MSL. The mountains ahead of us are 12,000 feet and possibly higher.

In order to take the revised route, I would have to climb up to 17,000 feet in altitude.

What is the big deal you ask? Well, a normally aspirated airplane really starts to run out of “oomph” at about 12,500 feet in altitude. That is why I stated, “Thank Goodness for turbochargers!” My turbocharged airplane is certified up to 22,000. We would not have been able to take the revised routing without the turbocharged engine.

While the plane may be certified to 22,000 feet, people are not. By FAA rule, the pilot must be on oxygen and the passengers must have oxygen available above 14,000 feet.

So, after being informed of the new altitude requirement, I broke out the oxygen hoses with nasal cannulas, hooked them to my portable tank, adjusted the flow to the appropriate level, and handed them to the passengers in back. The Angel patient, with her severe lung problems, was well versed in putting on “nose hoses”. I must admit I was concerned about taking her so high, but upon my inquiry, she gave me the thumbs up and she was doing fine.

So, we began the climb as we head toward the cumulo-granite (mountains for you Aggies out there). It was not CAVU at this point. There were broken cumulus clouds, although not thunderboomers, to the north of the pass. The climb starting at 12,000 was pretty brisk, but as we crossed 16,000 on the warm day with high density altitude, the climb rate for RizAir1 began to slowly drop under 500 feet per minute.

The controller called and advised I needed to get to 17,000 as quickly as possible. I was tempted to put on my best Scottish brogue and respond, “I’m giving her all she’s got, Capt’n.” Actually, I did respond “You are getting what she has to give.”

Well, RizAir1 gave what she had, and we did make it to 17k before running into the mountains. We were punching in and out of clouds as we headed towards the VOR south of Alamosa, CO. Our route took us just to the south of the peaks of Silver Mountain and Rough Mountain. The ride was smooth. Looking to my left, the south, I could see the line of building thunderstorms was blocking the pass. Again, Thank Goodness for turbochargers!

Being as high as we were, I asked ATC for a lower altitude the moment I had a visual on the Alamosa area. We had a small, portable 02 bottle, and three of us at 17k were draining it down rapidly. The controller had to keep us up a while longer, but, finally, upon passing the ALS VOR, he let us drop down to 15k which reduced the flow demand, and once past the Sangre de Cristo mountains on the west side of the valley, to begin a descent to 12,000.

As we were passing ALS, we heard a Cessna 182 on the frequency with Denver Center. It was apparent he was unfamiliar with the area and was discussing routing options with the controller. He mentioned he was headed for La Veta Pass. The frequency was not congested, so I asked the controller for permission to update the 182 pilot about current conditions. Pilots, like sailors and other travelers, often reach out to help others while on their journeys. It was also a bit of paying it forward in exchange for the controller’s help earlier.

I was able to advise the 182 pilot that he would not make it through La Veta Pass due to the build-up of CB clouds. I informed him of some passes further south in New Mexico that might not be blocked. He expressed his thanks.

The rest of the flight was uneventful, we made a visual approach into Farmington, and two hours and sixteen minutes from the start of the take-off roll, we were sitting in front of the FBO. The Angels were none the worse for wear, I had fun, and I think they did as well.

The controller in Denver went out of his way to help us out. He volunteered that the La Veta MOA had gone cold, worked us across the mountains and around the CB. I like to think that he would have done it anyway, but the Angel Flight call sign seems to open up the door just a little wider because the controller knows the nature of the “cargo” and that the pilot is donating his time and paying the expenses for the trip.

As with any job, having the right tools makes a significant difference in completing a task. On this trip, my instrument rating, a well-equipped airplane, and a turbocharged engine were all needed to make this mission a success. Thank Goodness for the turbocharged engine!

Clear skies and tailwinds!

RizAir – Blog #6